Christopher Columbus’s voyages to the New World changed history forever. Among his many discoveries: the pearl beds off the coasts of Cubagua and Margarita. The shimmering treasures he found, encountered during his third voyage in 1498, sparked a rush that fueled early European expansion.

For a pearl jewelry studio like ours, this story highlights the appeal of pearls and their deep historical roots.

The Spark of Discovery

Columbus first set sail in 1492, seeking a western route to Asia. Instead, he encountered the Americas. His initial trips brought back gold and cotton, but pearls eluded him. Then, in 1498, everything changed. While exploring the Gulf of Paria near modern-day Venezuela, he noticed native women wearing pearl bracelets. Intrigued, he bartered for them with simple items like needles and broken plates. The natives indicated richer beds lay to the west, leading later explorers toward Cubagua and Margarita. These islands would soon become known as the Pearl Coast, a name that echoed their riches.

Margarita, by the way, was named by Columbus after Margaret of Austria, a princess betrothed to the Spanish royal family. The name proved fitting, given the island’s eventual pearl bounty.

Columbus reported the pearls in letters and samples sent to Spain. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella valued them highly, as did European courts, but gold remained the ultimate prize. News of the discovery spread quickly through returning crews. Soon, the Pearl Coast became a beacon for adventurers.

This find didn’t just mark a new resource. It offered a quicker reward than gold. Ships returned to Europe laden with these gems, adorning royalty and clergy.

For our studio, this history underscores the value that pearls held in past cultures. Their traditional elegance is a quality we try to celebrate in every piece.

Cubagua and Margarita: The Pearl Powerhouses

Cubagua and Margarita quickly became the heart of the pearl trade. Cubagua, a small, arid island, hosted the first organized Spanish pearl-fishing operations around 1500–1502, with private ventures under royal licenses. The settlement of Nueva Cádiz was formally established by 1528. Margarita, larger and more fertile, developed fishing operations shortly after. Together, they formed a hub that drove Spain’s early colonial ambitions. The oyster beds here were vast, stretching across shallow waters that divers could reach with skill and endurance.

The process was straightforward yet brutal. Divers plunged into the sea, holding their breath to pry oysters from the ocean floor. Teams used small net bags or pouches tied around their necks or waists to collect their haul. The oysters were opened manually with knives on shore or aboard boats. This labor-intensive work made the islands a magnet for Spain.

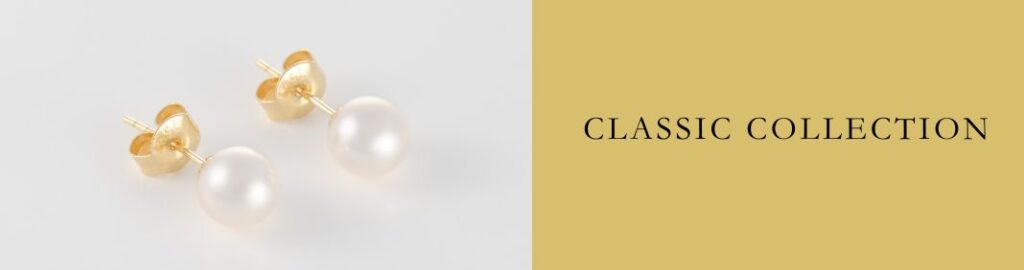

Meanwhile, the promise of wealth pulled settlers across the Atlantic. Ports buzzed with activity as ships carried pearls to Spain. Settlements grew, and Spain tightened its grip on the region. For us, this history inspires our Classic Collection, where pearls embody a storied past.

Pearl Fever: A Rush to Ruin

The excitement over pearls soon turned into a frenzy of greed. Divers, overseers, and merchants raced to harvest as many pearls as possible. However, this obsession came at a steep cost. The oyster beds, once abundant, couldn’t keep up.

From roughly 1500 to 1540, scholarly estimates based on Seville tax records suggest 10–20 million pearls were harvested from Cubagua and Margarita combined, with Cubagua accounting for the majority. Peak production occurred between 1520 and 1535. Spain’s royal fifth (quinto) records show annual exports averaging 200–600 marcos (roughly 400–1,200 pounds) of pearls in the busiest years, with higher peaks in some seasons.

But the harvesters ignored sustainability. Oysters need 5–10 years to form pearls, and wild beds yield a pearl in roughly 1 out of every 100–1,000 oysters. Instead of allowing recovery, divers stripped the beds bare. By the late 1530s, yields dropped sharply, and high-quality pearls grew scarce. In 1543, a hurricane and a possible earthquake-triggered wave severely damaged Nueva Cádiz on Cubagua. The settlement was abandoned by the mid-1540s. Margarita’s trade persisted longer but collapsed by the late 1500s. Overharvesting, combined with storms and shifting priorities, ended the boom.

This tale of excess resonates even today.

At Pearl Atelier, we value sustainability. We use cultured pearls grown on farms rather than pearls from wild pearl beds to ensure this resource remains a gift for future generations.

Enslavement of Pearl Divers: The Human Toll

Behind the glittering haul was a grim truth. The pearl boom relied on enslaved divers. At first, Spain turned to indigenous peoples. The Guayquerí of the Pearl Coast were skilled swimmers, forced to dive from dawn to dusk. Thousands of Lucayans from the Bahamas—prized for their breath-holding ability—were also enslaved and shipped to the islands, fetching high prices of up to 150 castellanos each.

The toll was devastating. Disease, exhaustion, shark attacks, decompression sickness (causing hemorrhaging), and intestinal issues from cold water killed divers rapidly. Whips and shackles enforced quotas. Native mortality rates reached 80–90% within a few years. By the 1520s, the Lucayan population of the Bahamas—estimated at 20,000–40,000—had been nearly wiped out through enslavement and disease across the Caribbean, with several thousand sent to the Pearl Coast.

As indigenous numbers dwindled, Spain increasingly relied on African slaves, who were seen as more resistant to Old World diseases. By the 1530s, Africans formed the majority of the diving workforce. The 1542 New Laws restricted native enslavement in general, though enforcement was uneven, and pearl diving remained deadly regardless of origin. Crews on Margarita often numbered 18–20, with strict quotas. Divers who exceeded quotas could sometimes sell the surplus, but failure meant debt or punishment.

This exploitation fueled expansion but left a dark legacy. Settlements thrived on forced labor.

Volume and Years: A Harvest Beyond Measure

From 1500 to 1540, Cubagua dominated production, with estimates of 8–15 million pearls over the period. Margarita contributed several million more, though records are less precise. The busiest years—1520 to 1535—saw the most intense harvesting. Tax records confirm the scale: peaks of 500–1,500 marcos annually in the 1520s.

Yet, this pace couldn’t last. By 1540, Cubagua’s beds were nearly exhausted. Margarita’s trade faded by the late 1500s. Attempts to revive operations in the 1600s failed. Today, small numbers of wild pearls are still found off Venezuela, but the great beds never recovered.

For pearl lovers, these figures dazzle. Our studio cherishes the history of pearls, offering traditional designs that revere the ancient natural gem.

Traditional

South Sea Pearls

Crafted for traditional elegance

A Lasting Impact

Columbus’s encounter with pearl beds did more than line Spain’s coffers. It spurred expansion, drawing settlers and ships to the New World. Cubagua and Margarita became stepping stones, proving the Americas held riches beyond gold. Nueva Cádiz was one of the earliest Spanish towns on the mainland Americas, with stone buildings and a church—a testament to their ambition.